In this year’s GIR, we will show you why and how changing the way we work (to be more inclusive, accommodate diverse needs and allow for better balance between work and other life spheres) matters — especially in this time of historic skills shortage. As also seen in the best practice cases, changing organizational structures and culture will allow for a winning scenario for everyone.

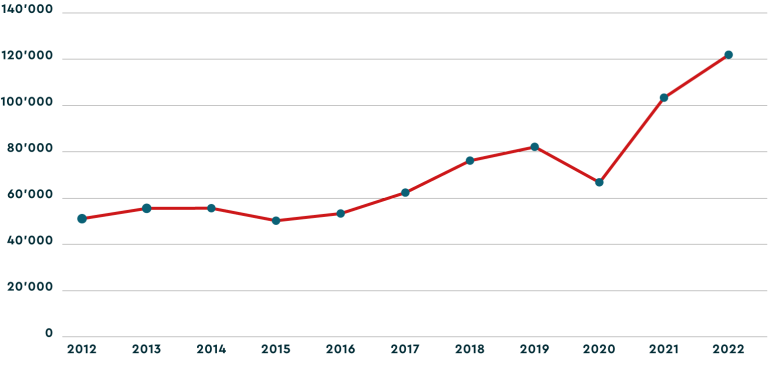

There is rare agreement among labor market experts that the skills shortage in Switzerland is acute. In 2022, the Swiss Skills Shortage Index (which compares the number of open positions with the number of job seekers in that specific area) reached a record high (up 68% compared to the previous year!) (Adecco, 2022). The skills shortage is particularly acute for the healthcare sector, IT, engineering, data science and machine learning, though there remains a slight skills surplus for more general administrative and assistance jobs and sales positions (Adecco, 2022). These trends will only intensify as more baby boomers retire (BSS, 2023).

In 2022, Switzerland had the lowest unemployment rate of the past 20 years! This is good news for employees – demand is high for them. For companies, finding suitable skilled workers is a growing challenge, especially with the baby boomer retirement wave in full swing. For older employees, the Swiss government is pushing to create attractive conditions for those at retirement age to continue working (or retirees to return to work) (Staehelin, 2023).

This means: Swiss employers have a problem. At the end of 2022 there were 34,000 more vacancies than registered unemployed people (FSO, 2023b). In terms of open vacancies overall, at the end of 2022, there were almost 122,000 positions (FSO, 2023b).

To combat skills shortage, companies need to do more with the talents they have, which means: Developing diverse talents, improving their work-life balance to increase their engagement and loyalty, and making sure they can work how they work best. Inclusive leadership, flexible work structures that fit with employees’ diverse needs, and measures to reconcile work with other life spheres are crucial in achieving this. This means: businesses in Switzerland should move past performative I&D measures and leverage policies to create a win for all employees (while boosting gender equity) and tackle skills shortage at the same time. To make substantial changes that will allow for sustainable success, we call on Swiss companies and organizations to do the following:

Through these actions, Swiss businesses will be positioned to enhance employee wellbeing, boost motivation, and incentivize people to stay at the company, helping to plug the leaky pipeline.

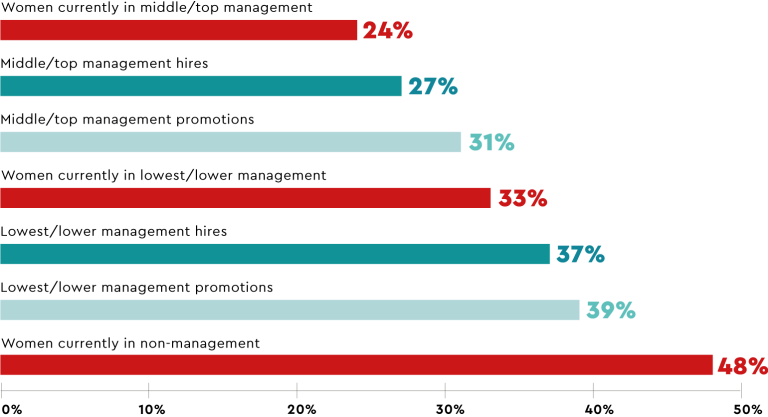

Imagine: What if your company made full use of its female talent pipeline? The status quo among GIR companies: Between non-management and lowest / lower management, the percentage of women drops from 48% to 33%. In middle / top management, there are only 24% women. This drop means that at each level, about a third of the potential female talent is “lost” due to the leaky pipeline. Even though companies have diverse talents, they are not developing them properly and thus not utilizing their full potential.

The longer jobs are listed, the longer work is not getting done – or existing employees must also cover the vacant position’s work, without extra pay. A BSS/ETH study finds that in Switzerland, jobs are advertised online for an average of 43 days. However, the vacancy duration varies enormously among the types of jobs. Around 1 in 10 jobs in Switzerland are online for over 100 days (BSS, 2023). This vacancy duration costs (a lot of) money. Because the jobs stay vacant, the Swiss GDP suffers annual losses of 0.66% overall, which corresponds to 5 billion francs a year. Compared to the overall GDP loss, the relative loss in the healthcare sector is more than doubled, and in the IT sector the loss is 5 times more than the overall Swiss GDP loss (3.4%) (Kaiser et al., 2023).

But finding new employees is only one part of the problem. Skills shortage makes it more important than ever to retain and engage talents that companies already have and develop them. And companies are currently not doing enough to achieve this.

The skills shortage is not just about “hard” skills and expertise. While technology-related jobs remain vacant the longest, an analysis of required (and desired) skills listed in advertisements reveal that there is also a “soft” skills shortage. An evaluation of vacancy duration, as a function of the competencies required in the job advertisement, suggests that a need for non-cognitive, interpersonal skills such as conscientiousness and empathy, social skills, and commitment also contribute to jobs going vacant for longer. (Kaiser, Möhr & Siegenthaler, 2023) These sort of “soft” skills are often associated with women: Research shows that women more effectively employ the emotional and social competencies correlated with effective leadership and management than men (Boyatzis et al., 2016). Filling the soft skills shortage — and with it, gaining key leadership skills — requires fully utilizing the potential of the female talent pipeline.

When it comes to promotions and new hires, companies are still leaving women “stuck” in the talent pipeline. This is particularly pronounced for the career step from non-management to lowest and lower management. Even though the share of women in non-management is 48%, the share among promotions is only 39%. Among new hires the share is only 37%. A lot of diverse talents are lost in the pipeline in part because these key promotions fall into “family primetime”.

The skills shortage demands a pivot in how companies value, engage, and utilize their skilled employees. Higher attrition rates and perceived lack of development opportunities are intricately linked, according to a recent survey of 1,000 employees from German-speaking Switzerland (GDI, 2023). Even without long vacancies, the cost of turnover is extremely high. It’s estimated that losing an employee can cost 1.5 – 2 times the employee’s yearly salary, with departures of more senior employees “costing” more than entry-level staff (Bersin, 2013).

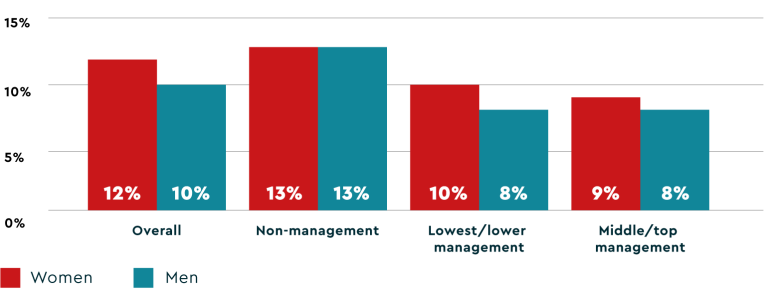

Which employee groups have particularly high attrition rates in management – i.e., who are the talents lost even as skills shortage runs rampant? The attrition rates of women in lowest and lower management levels are quite a bit higher than men’s. This means women in key springboard positions are leaving companies at higher rates than men. Companies should investigate whether this is due to a lack of perceived inclusion and career prospects, or because they have lucrative offers elsewhere. However, since women are less frequently hired at all management levels, the former is highly likely.

As seen below, the attrition rate is the ratio of exits to the number of employees at the end of the previous year plus new hires. The higher the attrition rate, the higher the share of employees of a certain group who are leaving!

Imagine: What if we had structures in the workplace and beyond that would enable well-educated women to shorten their family-related career break to a maximum of two years and return at a minimum employment percentage of 70%? Why 70%? According to the Federal Gender Equality Conference (SKG), this is the threshold at which enough money can be paid into one’s pension fund to stay financially independent in retirement. 55% of the currently 137,000 stay-at-home mothers are willing to return to work (FSO, 2021c). Assuming they were enabled to do this flexibly at an employment rate of 70%, we would gain an additional 52,745 full-time equivalents. Imagine the even bigger potential, if the average career break was only two years instead of five.

Swiss companies are in the middle of an unprecedented retirement wave. Never have there been so many new pensioners in Switzerland (FSO, 2023). At the same time, people in Switzerland have been having fewer children (FSO, 2023c; RTS, 2023). These demographic trends, labor force participation, and mortality rates can be extrapolated into the future. If there were no more immigration at all, the Swiss labor market would shrink by about 300,000 workers (approx. 5%) by 2030. If the current economic and job growth is maintained, about 340,000 jobs could not be filled in 2025. In 2030, the figure would be as high as 800,000 – about one in seven jobs (GDI, 2023). Filling this large a gap is not achievable even with very high immigration rates. Thus, “business as usual” will no longer be possible and we need to change the way we work.

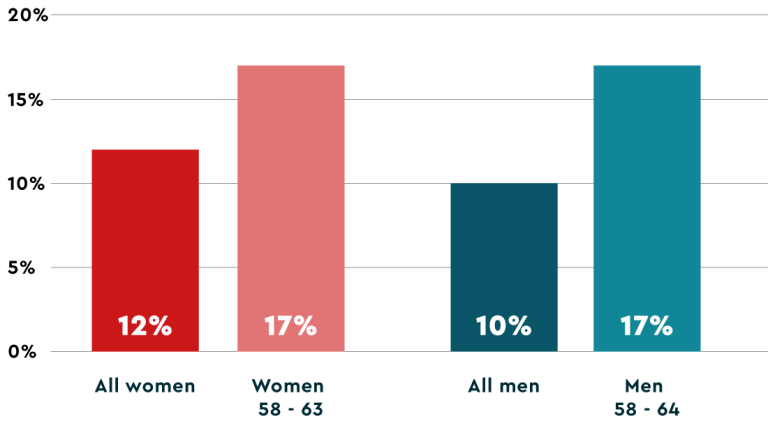

Early retirement is trending. Though women between 58 and 63 (pre-retirement age) represent only 7% of employees, they make up 11% of all departures. Men between 58 and 64 are 9% of employees and 13% of departures. Older employees who have often been with the company for decades have unparalleled knowledge and expertise. Early retirement isn’t always voluntary: Though the data does not reveal if these employees were forced to retire or went voluntarily, there is research that shows ageism (especially in tech) may cause “older” employees to be forced out (Rosales & Svensson, 2021). Companies should analyze the main causes for golden ager “brain drain” and take measures to combat it.

Retirement-agers are frequently hailed as a potential stop gap to skills shortage. Analyses by the FSO (2023c) show that the age group of 65- to 74-year-olds is still represented in the labor market with a labor force participation rate of almost 18%. The data also shows that part-time is the norm in this phase of life: Almost 80% of all people in this age group work part-time, most of them less than 50%. Over-65-year olds also represent a promising, nearly unutilized potential for GIR companies: The share of employees older than 65 is currently 0.3%. These employees work mainly in part-time positions.

At the same time, older employees are not seen as “talents”. Only 13% of promotions go to employees over 50, even though they make up 26% of all employees.

Companies must ask themselves and their older, highly knowledgeable employees what they need to continue providing their expertise. Research into the work preferences of people over 55 shows this demographic group is particularly motivated by work that they perceive as interesting, enriching, and as creating value and meaning (Wörwag & Cloots, 2018). Furthermore, many older employees would like to have more autonomy over the content of their work (ibid). Finally, their employer’s appreciation is particularly important to this group (ibid).

What can companies offer older employees regarding flexible career and work options? A rainbow career model is a promising approach: Older, senior employees have the opportunity not only to work less, but to give up some of their responsibilities to focus on core aspects of their expertise (for instance, a senior engineer might scale back people management responsibilities and focus on engineering) (Fischer, 2021; Buser, 2019).

Many employees leave their professional lives behind even before reaching official retirement age. From 2018-2020, 90% of 57-year-old men and 82% of women of the same age were active in the labor market. However, the labor force participation rate of 64-year-old men and 63-year-old women (i.e., one year before retirement) hovered around 50%. At 65, 36% of men and 28% of women were still professionally active. However, there are significant differences depending on the sector in the labor participation rates (FSO, 2021a). The 65- to 74-year-old age group is currently represented with a labor force participation rate of almost 18%. The data also show that part-time is the norm in this phase of life. Almost 80% of all persons in this age group work part-time (FSO, 2021b). This makes it clear that companies must offer specific models (e.g., partial retirement, downshifting, jobsharing, etc.) if they want to retain older, highly qualified employees successfully.

But how can companies leverage and retain their diverse talents? Companies can change the way they work and the structures in place.

Organizations

Managers

Individuals

Imagine: If paid work was equally distributed across men and women – that is, if the current full-time equivalents (FTEs) at work in Switzerland were distributed equally among all employees – everyone would work 83% (FSO, 2023d). Assuming we had structures that allowed everyone to pursue paid work a bit more at 85%, leaving enough time to split the unpaid care work among the genders equally, we would gain 87,360 FTEs across the Swiss workforce.

There are two basic ways to tackle skills shortage: Increase the number of employees or increase the efficiency of your employees’ output. Technological advancements are surely one part of the efficiency puzzle. The other is how we work, collaborate, manage, and lead – working culture. It is key to put adequate structures in place to promote an inclusive culture that allows employees in different life situations to work best.

Part-time and other forms of flex work – done right – can have demonstrable benefits to companies in times of skills shortage. After all, concepts like the 4-day week, agile working, work-life blending, top and job sharing, and the megatrend “New Work” have already been changing how we work for years. Technological advancements have made location-independent working normal in many fields and made employees – in theory – reachable 24/7, all while work has become more complex and faster-paced.

How is flexible work, when done right, good for business? Employees who are allowed to work the way they work best do better work. And employees who can balance work with other life spheres are more engaged at work, too. Here’s what the research says:

Imagine: A recent survey found that employees in Switzerland perceive 20% of their work as unnecessary (GDI, 2023). Among the activities mentioned are unproductive meetings, excessive emails, bureaucracy, complicated reporting lines and inefficient decision-making processes. If this perceived redundancy of 20% could be cut in half, organizations would gain an additional 437,000 full-time equivalent employees by freeing up person hours. This means: Use inclusive management tools and lead with trust to allow your employees to work how they work best. Make efficient collaboration and communication processes work for you.

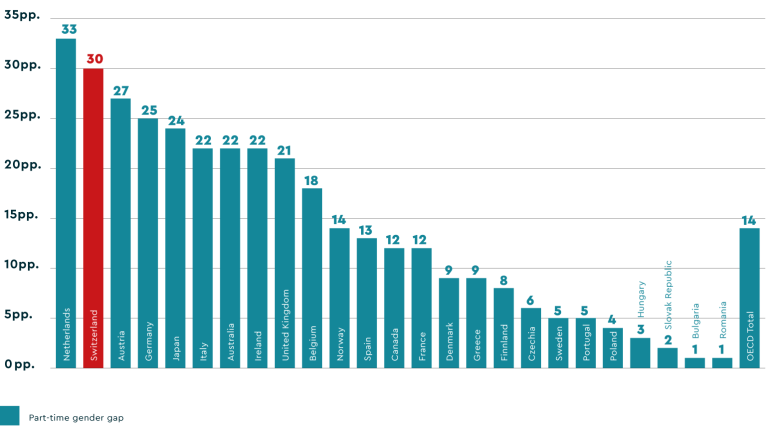

Part-time in Switzerland follows clear gender lines. Switzerland has one of the highest part-time gender gaps of any European country – twice as high as the OECD as a whole!

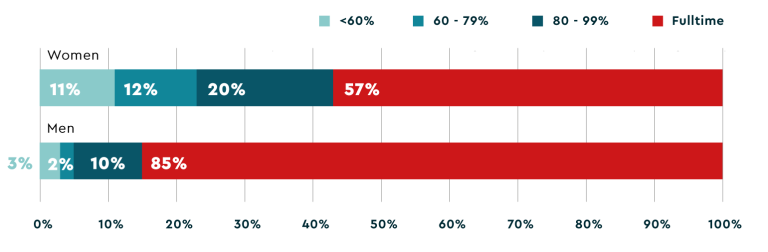

This is confirmed in the GIR dataset. While 43% of GIR women work part-time, the same is true for only 15% of GIR men. Moreover, 23% of the women work less than 80%, but only 5% of the men do the same.

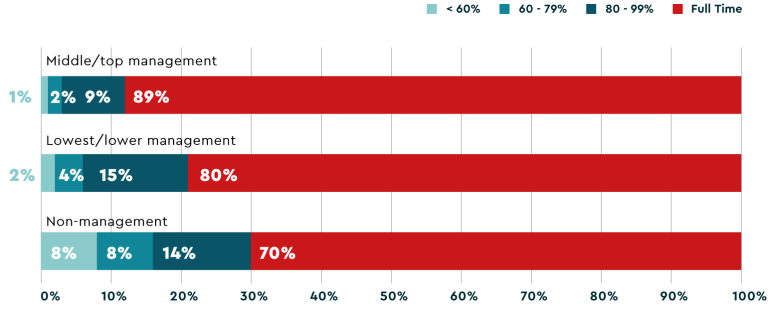

Leadership is still a full-time job in Switzerland. It doesn’t have to be this way. Advances in communication technology, agile work, and management models such as top-sharing and co-leadership for teams and projects already make both part-time and flex-time leadership lived reality in select companies.

Which leadership talents get “stuck” in the pipeline because of the rigid adherence to the full-time leadership norm? Roughly a third of part-timers in non-management will be held back because of their work percentage, or because companies cannot rethink leadership. The same is true for almost half of part-time lowest and lower managers!

While the average working percentage for women in non-management functions is 84% (and 94% for men), in management, the average is close to or significantly over 90% for all genders (women work on average 90% in lowest / lower management and 95% in middle / top management, men work practically full time across all management levels). The average employment percentage for women with personnel responsibility is 93% (99% for men). This means: Many women with lower percentages often are not even in contention – whether on purpose or not – for leadership positions.

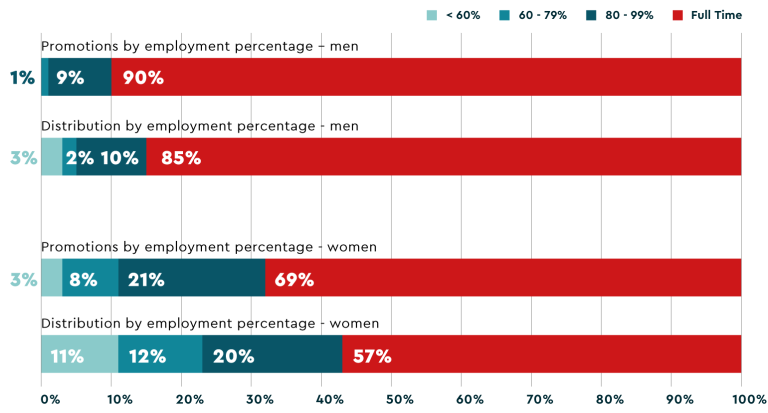

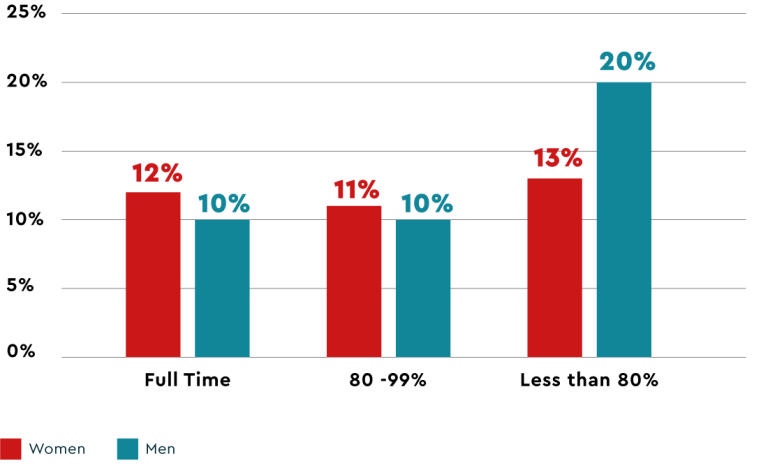

Especially for women, full-time employees have considerably higher chances of getting promoted. Even though only 57% of women work full-time, 69% of all women promoted work full-time.

The clear bias in favor of full-time managers also shows in hiring patterns. Compared to 57% of women who work full-time, 69% of female management hires work full-time. For men, the bias is less pronounced: 85% of men work full-time, as do 88% of management hires. Even though 46% of GIR companies advertise all leadership positions with the option for part-time, only 19% of all management hires go to part-time employees. This shows that companies might be talking the talk when it comes to part-time leadership, but not authentically walking the walk.

Fewer than 5% of management hires are employed at less than 80%, which is also the case for promotions. This means that 80% can be considered a clear lower limit at which it is possible to have a career still. Which begs the question: What part-time talents are currently invisible to companies?

A recent survey about the growing skills shortage caused an outcry in Switzerland because it proclaimed that part-timers (apart from mothers with young children) should work more to “solve” the skilled labor shortage crisis (Hermann et al., 2023). Media, politicians, and employer associations quickly call out part-time employment as the culprit for the skills shortage. This is a problematic fallacy. According to ETH labor market expert Daniel Kopp, “part-time work in Switzerland is synonymous with higher labor force participation” (quoted in Föry, 2023). Switzerland has one of the highest female employment rates of all OECD countries (GDI, 2023). If part-time were not possible, many of these women would not be in the labor market at all. In many industries, Switzerland combines the possibility to work part-time with comparatively conservative, traditional gender norms, according to political science professor Silja Häusermann at the University of Zurich (ibid). Switzerland has a structural and cultural problem, not a part-time problem.

According to the OECD, in Europe, only the Dutch have a higher overall part-time employment rate than the Swiss. But Switzerland has a particularly long standard work week. France’s work week has been 35 hours long since 2000 (Hayden, 2006). In Belgium, the working week is set at 38 hours (Kelly, 2022). By contrast, the average work week in GIR companies is 42.1 hours. This means another country’s full-time is our part-time. Consider that the Norwegian standard work week is 37.5 hours, equivalent to an 85% employment percentage in Switzerland. Coincidentally, this is almost the same as the average employment percentage of women in the GIR sample (86%)!

Belgium, Iceland, and Japan are some countries that are either testing or have already implemented a four-day work week (Smith, 2023). In France, managers cannot contact employees outside of office hours (BBC, 2016).

In addition, in many European states with a lower part-time employment rate, the state provides support structures that equalize care work responsibilities, such as heavily subsidized childcare and equitable parental leave (Koslowski, 2021). For example, in Vienna and Berlin, childcare is free for all parents (OECD, 2022). In Sweden, all parents are entitled to a total of 480 days of parental leave. Switzerland should look to adopt such policies and develop a “shared work, valued care” (Bailey et al., 2001) culture, which will require employer action and structural changes in the political and legal sphere.

Part-time is only part of the flex-work story. Thinking about New Work more broadly, how do (diverse) employees need to work, and how can companies best support them?

What is quite clear is that employees are unwilling to work more to fix the skills shortage. 68% of respondents in a recent survey in Switzerland believe that we are working too much (Hermann et al., 2023). The goal should be to work smarter, not spend more time at work, and do more with the employees you have.

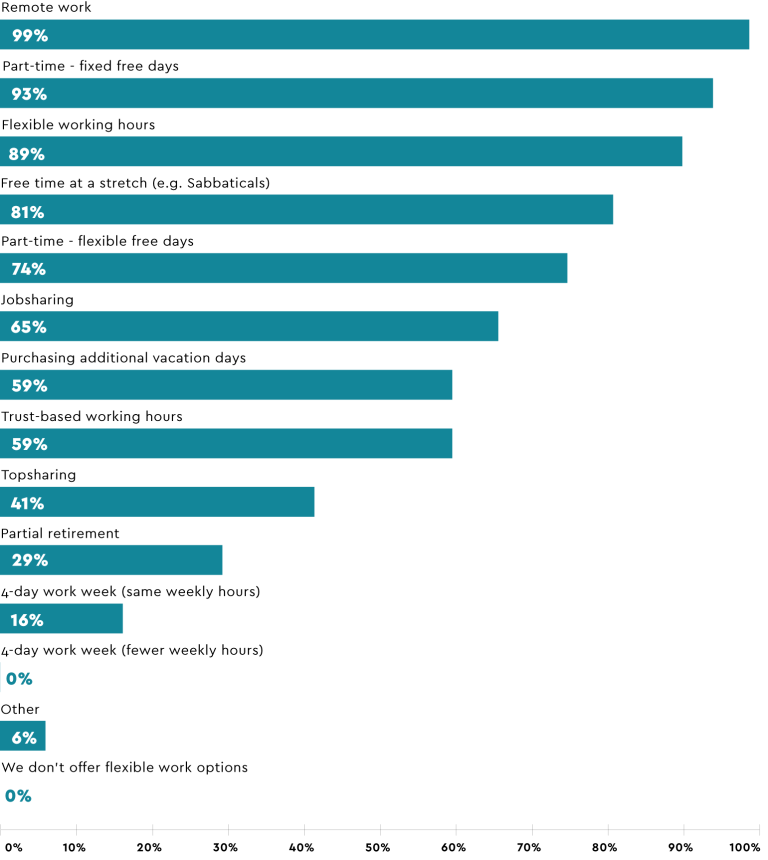

A survey carried out on behalf of the CCDI shows that almost 70% of respondents see flexible working hours and remote work as either important or very important (Ochsner, 2023). While these are offered by at least 90% of GIR companies, it is important to read the fine print. 77% of GIR companies have rules about how many days remote work is possible, and on average, employees are only allowed to work from home up to half the week.

There are also clear discrepancies between what companies offer in terms of flex work and what employees want. 54% of surveyed employees would find the offer of a four-day work week (at equal salary) important to very important, but no GIR companies offer this model (and only 16% offer any kind of 4-day work week option) (Ochsner, 2023).

Internationally, the 4-day week has already been thoroughly tried and tested. Iceland experimented with the reduced week of 35 hours with full pay in large-scale field trials and saw extremely encouraging results. Despite reductions in working hours, productivity and performance were maintained or even increased (Haraldsson & Kellam, 2021). It is important to note that working hours were not simply reduced, but work processes, communication and decision-making levels were also optimized in the course of the experiment. Another example of alternative work week comes from Belgium, where employees have the option to compress a 5-day workweek in 4 days by augmenting the daily workload to 9.5 hours. In Switzerland, organizations and companies are still very cautious about testing whether and how a 4-day week can work. Interestingly, considering the hours actually worked in Switzerland in 2021 by employed persons (i.e., including overtime and deducting absences), the result is a weekly working time of 31 hours (FSO, 2022a). To exaggerate, it can be said that Switzerland has already arrived at 31-hour week.

There is often an assumption that flexible work is mainly a key concern for employees with young families. The same survey shows this is not the case: the share of respondents who consider reconciling professional and non-professional activities as (very) important barely differs between generations (Ochsner, 2023).

The need for flexibility at work is trending upwards and will only intensify over time. Data from the FSO on part-time work by generation and gender show that men work part-time more often in younger generations. For men at age 35, 6% of Baby Boomers worked part-time, 9% of Generation X, and among Millennials (Generation Y) the figure is already 14% (FSO, 2019). Among 35-year-old women across all generations, slightly more than 60% work part-time (FSO, 2019).

Especially among the younger generations, employers can score points with flexibility and time off, e.g., in the form of sabbaticals, parental leave or childcare. While Generation Z finds the strict separation of work and career important, a work-life blend is perfectly fine for Millennials. However, Millennials tend to find rigid working hours unattractive (Mercer, 2022). This, too, means that companies need to take a multi-generational, intersectional approach.

In 1933, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that technological progress would result in a 15-hour workweek by 2030 (Keynes, 1930). He assumed that productivity would increase with machine use, so reductions in working hours would be possible without sacrificing a high standard of living. We are still a long way from a 15-hour week. The length of the standard work week was established around the time of the Great Depression and has not meaningfully decreased since. Isn’t it high time we rethink how we can work better?

What does all this mean for companies? To level the playing field, changing the work norms is crucial. This change includes organizational culture, type of leadership, and structures (both at company and political levels). Companies must trust employees to know what works best for them. This way, companies can create a win-win-win scenario, where inefficiency is minimized, employee engagement maximized and needs of diverse employees filled.

Organizations

Managers

Individuals

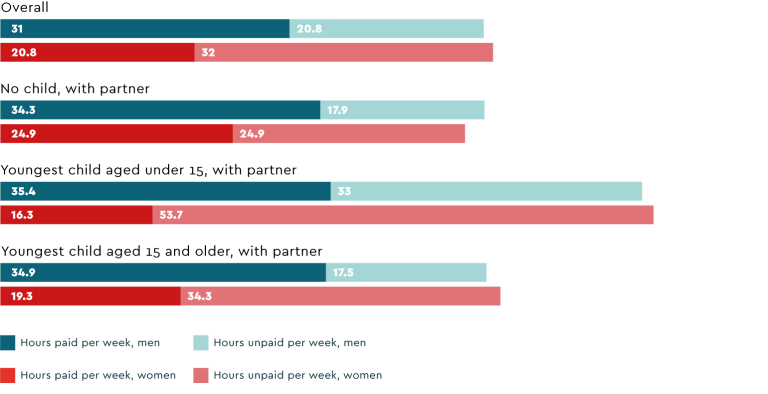

Imagine: If men took on half of the unpaid work that women currently do more (11.2 hours), women would have 5.6 hours more at their disposal to pursue paid work. This time corresponds to 13.3% of a Swiss standard working week of 42 hours. With 1,732,000 full-time equivalents currently worked by women in the Swiss labor market (FSO), this would amount to a staggering additional 230,356 FTEs. Even in a more conservative scenario, calculating with a quarter of the 11.2 hours “overtime” that women currently do unpaid, the gain would amount to a decent 115,178 FTEs.

Care-worpaidk inequality highlights the unbalanced distribution between paid and unpaid work and responsibilities. That men are treated as providers (rather than fathers) and women as caregivers (and not career women) is perhaps the driving factor of career inequality in the Swiss workplace today. This inequality is detrimental to women’s careers and men’s fatherhood roles and exacerbates the skills shortage by removing women from the internal and external career pools.

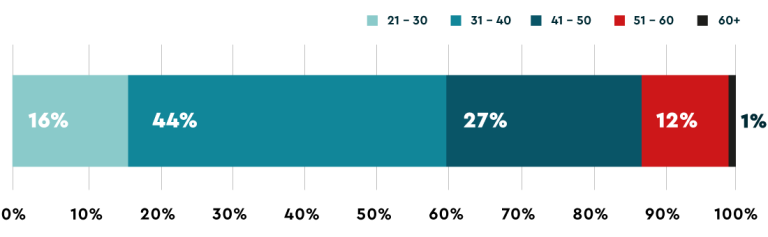

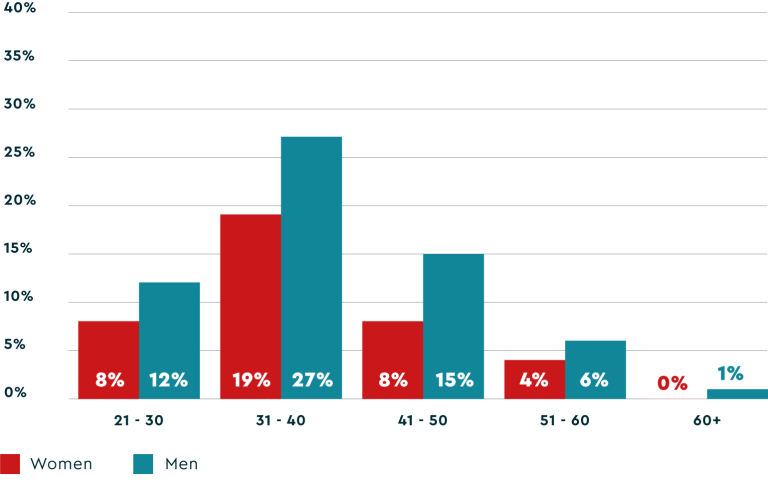

The traditional Swiss career model assumes that key career steps are taken between 31 and 40. 44% of all promotions go to employees in that age group, even though the group only comprises 28% of the workforce. At the same time, the average age of women at the birth of their first child is a little over 31 years (FSO, 2023a). This indicates that Swiss companies are clinging to a traditional career progression model rather than a lifecycle-oriented one (sometimes kaleidoscope model).

Research clearly shows that working mothers are often reduced to either a stereotype of “homemaker” (warm but not committed to her career) or as competent but cold career women. The latter type is also harmful to women’s careers, as these women are seen as deviating from the commonly held stereotypes about how women should be and behave, and thus untrustworthy (Cuddy et al., 2004; Odenweller et al., 2020). Mothers are seen as less competent than both childfree women and fathers (Fuegen et al., 2004). This perspective applies to pregnant women as well (Morgan et al., 2013; Paustian-Underdahl et al., 2019). These biases even extend to women of a particular age who may potentially become pregnant because of the perceptions of risk to an employing organization (Gloor et al., 2022).

Swiss businesses still adhere to an antiquated view of families. This view is heteronormative and sees women as the primary caregiver when families begin to have children. This result is the “motherhood penalty,” a gap between men’s and women’s career opportunities and earning potential that begins before the first child’s birth and continues after birth (Budig et al., 2010). This penalty period continues to grow until children reach school age. Because of the motherhood penalty during the family primetime period, key talent remains “hidden” because the skills of mothers are overlooked. Check out the recommendations to understand how to make these talents visible.

Imagine: What would happen if companies promoted women according to their share in the talent pipeline? In the upcoming 5 to 10 years, a considerable number of employees will retire. Assuming the retirements in lowest and lower management are getting replaced by promoting employees from non-management and promotions were proportionate to the gender distribution in non-management (48% of promotions going to women), the share of women in lowest and lower management could be increased from 33% to 37% in 5 years and to 44% in 10 years. In middle and top management, if 33% of the vacant positions were filled women, the share of women on that hierarchy level could be increased from 24% to 34% in 5 years and 37% in 10 years.

While men and women work at a very similar percentage between 21 and 30, the part-time gap in favor of men widens to 12 percentage points between 31 and 40 and 14 percentage points between 41 and 50. Though in certain situations individual couples may choose to reduce employment percentages, that choice is still made based on Swiss societal norms and legal structures (such as lack of subsidized childcare, marriage penalty in the tax system, or inequitable parental leave policies). That is why, as seen in the figures, it is during this family primetime period that the gap between employment percentages widens drastically.

A study on the long-term impact of parenthood on gross earnings found staggering differences between men and women. While the earnings of men and women evolve similarly before parenthood – after adjusting for life cycle and time trends – they diverge sharply after parenthood. Women experience a large, immediate, and persistent drop in earnings after the birth of their first child, while men are essentially unaffected. Scandinavian countries feature long-run penalties of 21–26 percent, English-speaking countries of 31–44 percent, and German-speaking countries feature penalties as high as 51–61 percent. (Kleven et al., 2019)

Conversations around careers implicitly focus on paid work, but what if we took unpaid work into account? Factoring in paid and unpaid labor, men and women work roughly the same number of hours a week, though women spend more time on care work that goes unpaid. This means, naturally, that many women cannot take on more paid work.

The division of labor of homemaker and breadwinner was first established during industrialization. With a strict division of working and family life according to gender, this division continues to shape our understanding of work and working hours (Baumgarten, Burri & Maihofer, 2017). These norms are “sticky”: Women still take on the majority of housework, particularly in households with children. Thus, in just under 70% of heterosexual couples with children (aged 25 to 54), housework is mainly done by women. The division is somewhat more even among couples without children; about half of them do household chores together. In 40% of these couples, the woman is mainly responsible, and in only 8% is the man mainly responsible (FSO, 2022b).

Having children not only influences the distribution of housework, but also affects women’s employment. In more than 60% of families, the model with a full-time working father and a part-time working (employment level <89%) mother is still prevalent. Less than 10% of couples with children choose a model in which both are employed part-time; about 15% work full-time (employment level 90-100%) (FSO, 2022b). The birth of a child has only a minor impact on the labor force participation rate of fathers, though their salaries tend to go up as well as their career prospects (Misra & Strader, 2013; Bygren et al., 2017).

Today, we see the financial consequences of women’s part-time employment in Switzerland mainly. The unequal division of gainful employment, housework and family work affects the amounts saved and leads to differences in the corresponding benefits (“Gender Pay Gap,” “Gender Pension Gap”; Federal Council, 2022). Part-time models could analogously lead to a “part-time pay gap” and a “part-time pension gap.” Most families with children choose part-time models, but only a few think about the household budget (39% of Swiss parents) and even fewer about the consequences for their pension provision (27%) (SwissLife, 2019). This lack of planning is particularly problematic in the case of divorces when the same money must be stretched across two households. Additionally, in Switzerland a decision of the Federal Tribunal has implemented a strict interpretation of Art. 125 CC, indicating that the principle of self-sufficiency applies to post-marital maintenance with the consequent obligation to reintegrate into the employment process or to expand existing employment activities (Federal Tribunal, 2021). In other words: Post-divorce alimony is now scarcely granted.

Among the 30 OECD countries, Switzerland is third last regarding length of total parental leave – only the US and Mexico offer less!

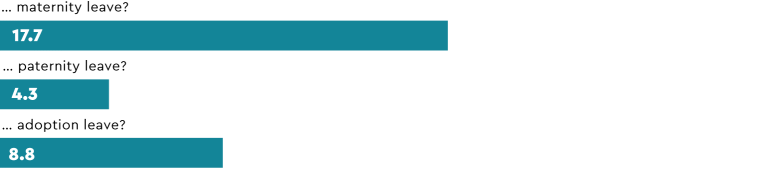

In Switzerland, mothers are legally entitled to 14 weeks of maternity leave. Leave must be taken all at once; if mothers return to work any time after eight weeks, they are no longer entitled to their leave days. The average number of weeks GIR companies offer is slightly higher at 17 weeks. For fathers, the legal minimum is two weeks, the average length in GIR companies is 4.3 weeks. In contrast to maternity leave, paternity leave is not mandatory and can be taken piecemeal. An example might be taking two weeks directly following the birth of a child, and then working 80% for ten weeks. Many fathers don’t take the full paternity leave they are entitled to. Some take none at all. Only 70% of fathers have taken the full two-week leave since its introduction in 2021. Surveys show that more fathers would like to take paternity leave but feel that their employer does not want them to (Sibold & Thurnherr, 2022). Note that the average GIR company offers almost nine weeks of adoption leave, which is over twice as long as paternity leave, further emphasizing that fathers are not seen as equitable care givers.

Only 16% of participating companies offer equitable parental leave. It is important to read the fine print. Even if a company offers “inclusive” parental leave (for instance 26 weeks of parental leave for the primary parent, 6 weeks for the secondary parent), they may include a clause that automatically designates the birthing parent as primary caregiver.

A study from Germany showed that with shared parental leave, women return to work more quickly and at higher employment percentages (but this effect only becomes apparent if fathers take more than the minimum paternity leave) (Frodermann et al., 2023). Paternity leave increases the social expectation of men to take over parts of the child-rearing work. Another study compared women’s labor market participation before and after the introduction of paternity leave in 31 OECD countries. The study concluded that paternity leave contributed, on average, to a 5% increase in female labor market participation (Fernández Bettelli, 2020). A Spanish study found that 12-year-old children of fathers who had been able to take paternity leave showed more egalitarian gender perceptions, and were more supportive of balanced labor market participation between men and women (Farré et al., 2022). Longer paternity leaves are one of the keys to gender equity in the workplace.

Although the work-sharing model in Swiss families with children is often still very traditional with the man working full-time and the woman part-time (approx. 41%) or not working (approx. 11%) (FSO, 2022b), surveys show that both women and men (in the German-speaking part of Switzerland) have expectations that differ from lived reality. Men who currently work full-time consider an 80% workload as the ideal workload for fathers and 50% paid work to be the ideal part-time workload for the mother. Men who are already working part-time (employment level <90%) see 60% as an ideal workload for both parents (Bütikofer et al., 2021). Women working part-time would prefer the 80:50 model, women working full-time would prefer the 80:60 model (Bosshard et al., 2021). However, higher education levels are associated with a more equitable view of the ideal work percentage distribution.

This shows that while traditional gender norms around paid work persist, the Swiss “full-time norm” is seen as outdated by all.

A recent survey of Swiss men showed that younger men (up to 34) find it a burden to be the “main breadwinner” in the family. About half of the men would reduce their workload if possible but cannot do so for financial or professional reasons (Bütikofer et al., 2021).

Since the Millennials entered the workforce, work-life balance and an “equitable” family model in which both parents do their fair share of paid and unpaid work have become significantly more desirable (Thalmann et al., 2023). For example, seven out of ten men under 25 favor parental leave of several months, which parenting couples can flexibly arrange and take. This is significantly more than among 35- to 64-year-old men (43%) (Bütikofer et al., 2021).

At the same time, many women working part-time would work more if conditions were different: 37% of women currently working less than 80% would like to increase their workload if there were more flexible and better childcare structures, 25% if working hours were more flexible, 15% if home office were available (Hermann et al., 2021).

Fathers who do their fair share – and thus go against established norms – are often penalized. While taking on a care role is commendable for mothers, the opposite is true for fathers. This is also reflected in studies:

Our analyses show men who work less than 80% have a considerably higher turnover rate compared to their full-time counterparts, and also compared to women who work part-time. This indicates that Swiss working cultures do not include men who act outside the established (work) norms.

Organizations

Managers

Individuals

It’s been over 50 years since Friedman said the sole responsibility of a business was to increase profits (Friedman, 1970). Doesn’t Friedman’s idea seem antiquated, like how Swiss businesses view families? Swiss business must change to fix the leaky pipeline. If we are to make progress and create true gender equity, priorities need to shift. Employee wellbeing and an embrace of new working models must be at the top of organizational focus.

As we conclude the big picture, think about how this shift in priorities relates to closing the multiple gaps that have been discussed. Remember to 1. Leverage all your diverse talents 2. Rethink rigid work norms to be more inclusive 3. Ensure parental leave policies are equitable for mothers and fathers. Last year we said the gender gap in Switzerland could end by 2042 if we all do our part. Let’s work together to shift societal norms and shore up the leaky pipeline so that gap closes quicker. For more on how to act, see the recommendations.