Realizing any meaningful version of meritocracy depends on many principles and practices falling under the umbrella of “DEI.” Inclusive meritocracy is more important than ever given our demographic challenges. How so?

To find the best candidates, companies need to have access to the biggest possible pool of candidates with diverse skills and perspectives. If diversity is not part of the hiring strategy, some employers will be at a distinct disadvantage.

Claiming to hire or promote the “best” only works if one can access the broadest possible talent pool and rely on objectivity and a level playing field.

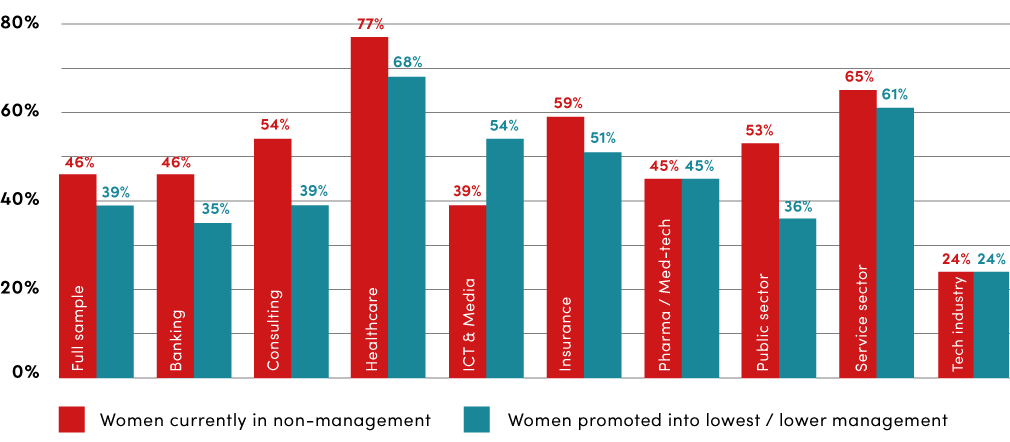

Are companies accessing the full, diverse talent pool right now? Companies are not fully utilizing the external talent pool. For example, while women make up 46% of non-management — and 47% of the overall working population in Switzerland (FSO, 2024x) their share in lowest/lower management hires is only 39%.

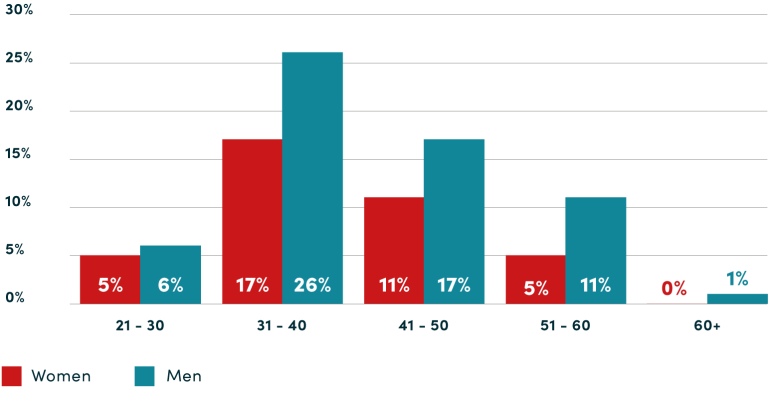

The under-utilization of female talents when it comes to hiring becomes even more apparent when we look at management hires by gender and age. Past age 30, the share of women among management hires becomes smaller and smaller. In other words: Companies are not able to access the full talent pool when it comes to hiring.

A study of hiring behavior on a large Swiss job platform clearly shows: Recruiters tend to spot talent and potential more easily where they expect to find it – a bias (Hangartner et al., 2021). For example, rates of contact by recruiters are 4–19% lower for individuals from immigrant and minority ethnic groups, depending on their country of origin, than for citizens from the majority group. Women experience a penalty of 7% in professions that are dominated by men, and the opposite pattern emerges for men in professions that are dominated by women (Ibid).

The first promotion step from non-management to lowest/lower management is an interesting place to evaluate if meritocracy is at play. In non-management, gender representation is close to 50:50, and the first promotion level is often reached earlier in one’s professional life in the younger age groups, where the genders are the most equal regarding experience, education levels and employment percentages. In fact, women are also overtaking men in the under-35 age group when it comes to tertiary degrees, which will have significant effects on the workforce over the coming years (FSO, 2025).

With such a level playing field, one would expect promotion rates that reflect the talent pool’s potential, indicating that promotions are meritocratic. However, women’s promotion rates in most industries are far below the talent pool’s potential – i.e., they are likely not meritocratic.

In the full sample and in six out of nine sectors, the percentage of women among promotions to lowest/lower management is lower than their share in non-management. The most significant differences are in the public sector (17 percentage points), consulting (15 percentage points), banking (11 percentage points), and healthcare (9 percentage points). Pharma/med-tech and the tech industry promote equitably. In ICT & media the percentage of women among promotions is higher than in non-management.

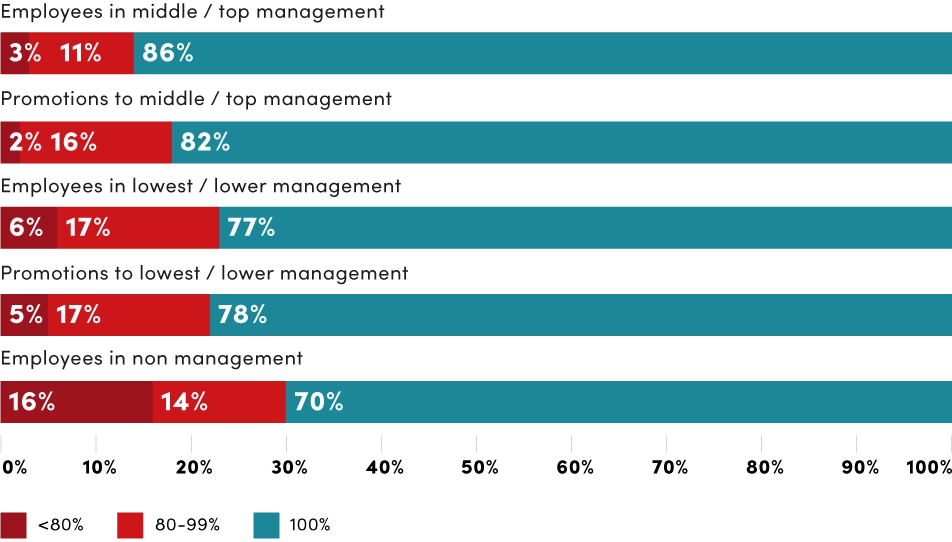

Another case, where it becomes clear that the current business world is not meritocratic: Employees working less than 80% are less likely to get promoted. In other words, the system fails to recognize performance and impact beyond hours logged, and presence is still seen as equal to performance.

The significant gender part-time gap of 27 percentage points in the sample analyzed for this report (43% of women and 16% of men work part-time) shows how the current merit system disadvantages women, mainly because it tends to favor those in full-time roles. The OECD notes a 30-percentage-point gender part-time gap for Switzerland, that is, the second-highest in Europe (OECD, 2025). This also overlooks the value of unpaid work, which is more frequent among women who still take on the lioness’s share of care responsibilities in Switzerland. On average, women spend 12.1 hours more per week on unpaid work than men (FSO, 2025x).

Realizing genuine meritocracies will remain elusive as long as men and women have to operate under unequal conditions regarding compatibility topics.

”While terms like diversity, inclusion, and flexibility are often highlighted, deeper structural issues are rarely addressed. For instance, competitive elbow-culture or the systemic reliance on unpaid care work to sustain family life is seldom questioned. In my experience, workplace culture is shaped far more by hierarchies and competition than participation or care.” – Survey participant, Workplace Culture Survey, 2025

When having the “right” age counts as merit, “best” talent can be overlooked.

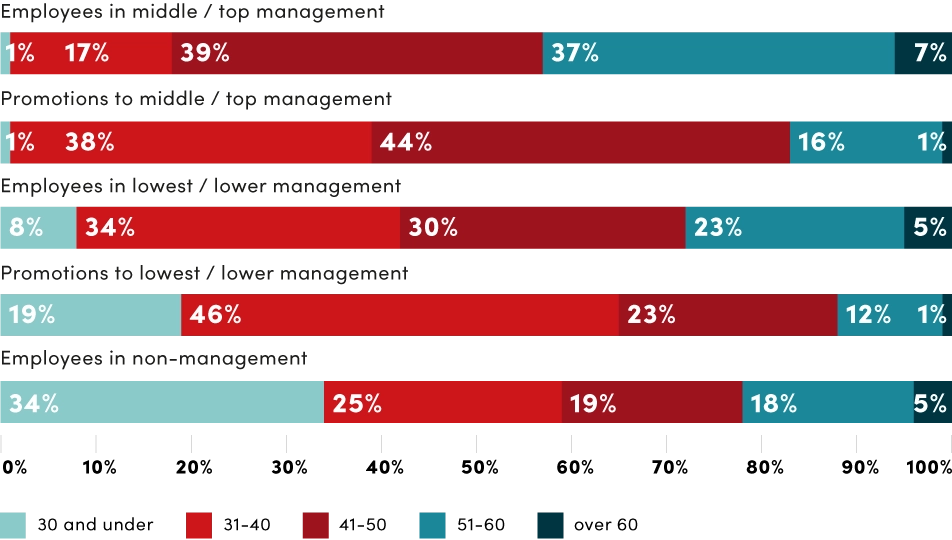

Looking at promotions by age shows that the age groups 31-40 and 41-50 are over-proportionally considered for promotions to lowest/lower and middle/top management, compared to their share in the talent pool: Employees between 31 and 40 only make up 25% of non-management, but with 46% almost half of all promotions to lowest/lower management. Age group 41 to 50 makes up 30% in lowest/lower management, but 44% of promotions to middle/top management.

Fostering and investing in talent relatively early in their life cycle makes sense for an organization, as it may expect a long-term return on investment. Work experience is often a factor, but this is not always linear with age. Some people may be in the army for a few years, others take time off to travel, and others work part-time because of care responsibilities, an engagement in politics, or voluntary work. Therefore, expecting and spotting “best” talent in certain age groups rather than in others is also a bias that can be in the way of finding the “best person for the job”. Perhaps it is a 50+ woman who had a career break earlier in her life and therefore a slower career progression than her male peers, or it might be a young talent under 30.

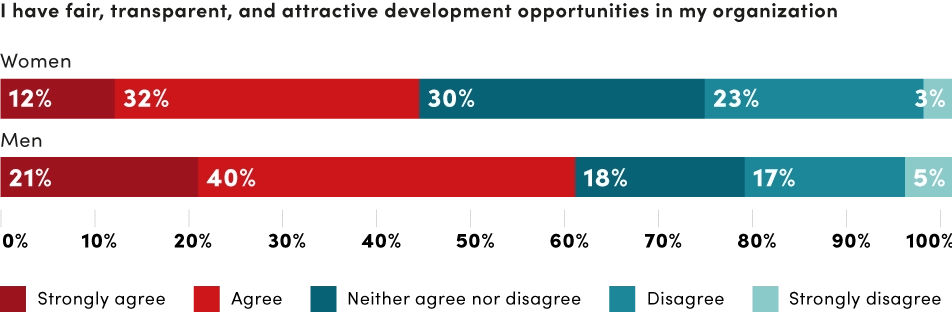

Only 44% of female and 61% of male talents agree or strongly agree with having fair, transparent, and attractive development opportunities. In other words, 56% of female talents lack concrete perspectives to advance. Even worse, 26% of women and 22% of men disagree or strongly disagree that they have fair, transparent, and attractive development opportunities. If a quarter of the workforce feels excluded from access and opportunities, chances are high that meritorious talent will be overlooked. – Reaching meritocracy is still a long way off.

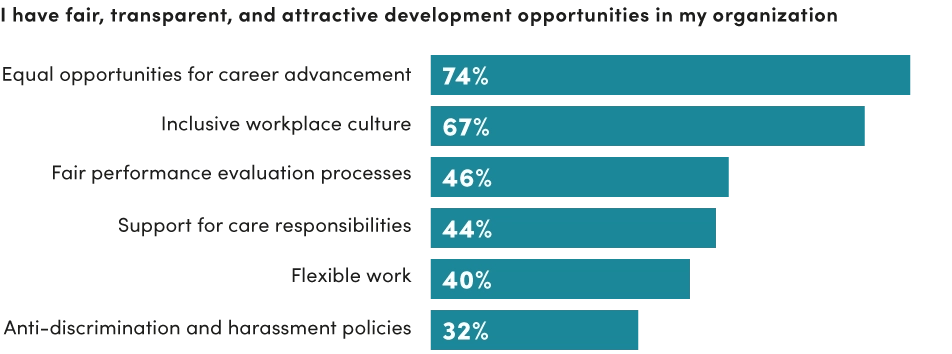

What can companies do better regarding DEI, according to their employees? With 74% by far the most mentioned and ranked as number one for women, and in third place for men, are equal opportunities for career advancement. This indicates that women are being impacted more by the lack of meritocracy than men, though it affects all genders.

”The promotion processes are hard to navigate because they are so non-transparent. Some mindsets are: “If you have to ask for a promotion, you are not ready for it.” – Survey participant, Workplace Culture Survey, 2025

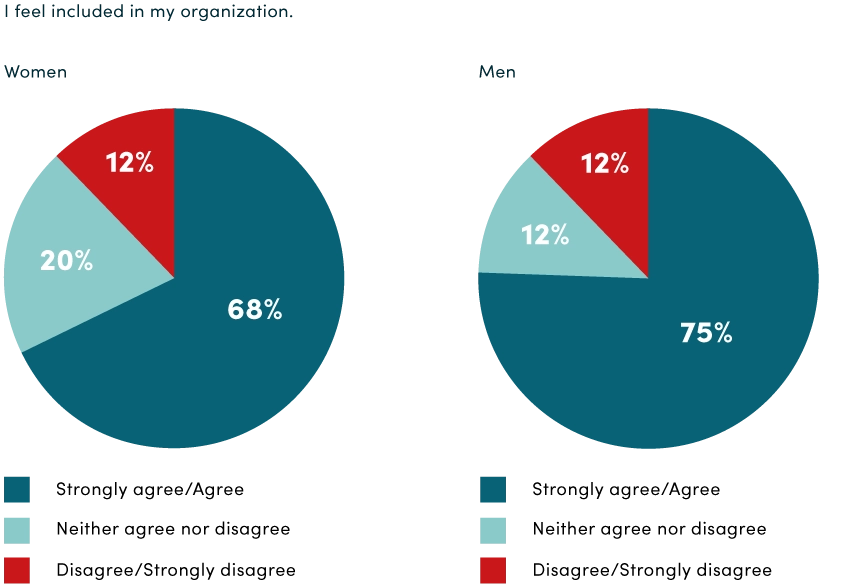

In other words, only 75% of men and 68% of women feel included in their organizations. This is a problem, as inclusion and belonging drive employee engagement and loyalty. Clearly, inclusive leadership is relevant for all employees. Of the respondents, 83% of men agree or strongly agree that they feel valued and respected by their managers, compared to 76% of women. There is much room for improvement.

Companies championing inclusive meritocracy get the best of all business worlds: They hire and promote the best and have engaged and loyal employees.

Take the Meritocracy Check HERE!

Find out how meritocratic your organization is today and where to start to raise the bar